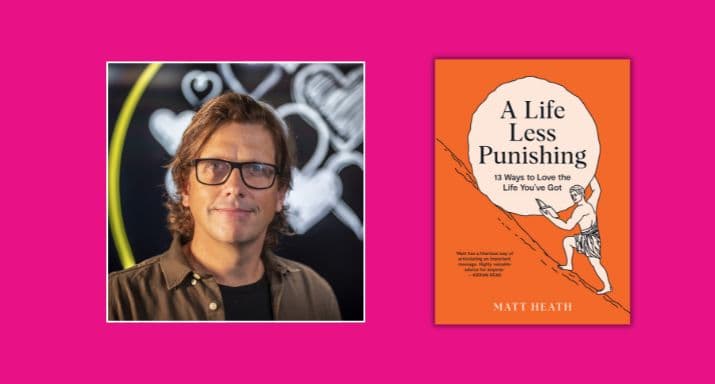

Extract: A Life Less Punishing, by Matt Heath

Why is it that no matter how good things get, we still feel dissatisfied? A few years ago, Matt Heath decided to find a way to live a life less punishing. He took a deep dive into why we feel the way we do and how to change it, interviewing leading international thinkers in neuroscience, philosophy, biology and psychology on the reasons behind our unwelcome emotions: anger, worry, stress, loneliness and many more.

Are you grumpy, bored, stressed, or blowing up over stuff that doesn't matter? Then read this book. Turns out, once you have the tools to unpack and take charge of your emotions, life gets better - for you, your mates and your family.

Extracted from A Life Less Punishing: 13 Ways To Love the Life You've Got by Matt Heath, published by Allen & Unwin NZ, RRP: $37.99

Chapter Three

Scared?

It’s the winter of 2003, and a friend has scored me a job as the overnight security guard at an abandoned and allegedly haunted Victorian debtors’ prison in London. A film crew is shooting till 9 p.m. each night and they need someone to stay over and watch the equipment until they return at 7 a.m.

The Whitecross Street Prison, or ‘Cripplegate Coffeehouse’ as it was known when it opened in 1815, quickly gained a grim reputation. Charles Dickens mentions the place in The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club as an example of a particularly bad prison one should try to avoid being sent to. In eighteenth- and nineteenth-century England, destitute persons were incarcerated in debtors’ prisons until they secured outside funds to repay the debts. There’s an obvious catch-22 here — how do you make the money to get out while you’re inside?

In 1847 journalist Nigel Cross wrote ‘the crying evil of Cripplegate is that the unfortunate debtor had no means of protecting himself from association with the violently depraved’. In this building I am guarding tonight, hundreds of people once went insane and some took their own lives.

All this weighs on my mind as I trudge with my weak torch into the lower levels to make sure the film equipment hasn’t been damaged by the water constantly dripping from the roof. They switch the power off at night, and the prison feels like a deep, dark tomb. Crawling through the rows of cells too small to stand in is bad, but wading through ankle-deep black water in the basement peaks my fear to new levels. My neck hairs are sticking straight up.

Then . . . I hear a splash in the far corner of the basement. I swing my dim torch wildly around, but see nothing. I ask — in a high-pitched squeak — ‘Is anyone there?’ Another splash; maybe a rat, maybe a poltergeist — I let the fear in and it takes over completely. A massive scream rings out, possibly from me but more likely from the tortured soul of an indebted Victorian pauper.

I run about five metres before tripping head-first into the cold water. The torch battery dies. My heart is pounding out of my chest. The ghoul draws nearer — I can definitely hear him now. He’s stomping and splashing through the black water. Closer and closer.

Then I see him. Kind of. A split-second glimpse of a tall, pale-blue man with messy grey hair. I jump up and run towards a shimmer of grey light, scamper through it and bolt up the stairs, tripping multiple times before exploding out the big metal door onto the street, where I back onto the road and nearly get hit by a black cab. ‘Get off the road, you absolute helmet!’ the driver yells (or something similar).

Too scared to return, I abandon my post for a pub down the road and spend my entire £100 nightly prison pay drinking. In a drunken stupor, my mind circles back to that supernatural incident. Who — or what — tried to kill me?

Then it hits me. It was Christopher Walken from Tim Burton’s 1999 supernatural horror flick Sleepy Hollow. In the movie he sports piercing, pale-blue eyes, yellow fangs, and a large black rider’s coat with an ornate silver-metal armoured vest underneath. This all makes sense now. I’d seen the movie on DVD a week before while coming down off acid.

While it seems unlikely that Christopher Walken is actually lurking around in costume in the basement of a London debtors’ prison, there’s no way I can re-enter Cripplegate tonight; far too scared. When the pub closes, I take up a vigil down a nearby street, surveying the prison door like a trembling rabbit might watch a dog that wants to eat it.

This part of town is much more dangerous outside at night on the street than locked in safely behind a large metal door. But such is the irrationality of fear.

At 6.59 a.m. I re-enter the prison, but only halfway into the entrance. The crew arrives, and I act as if I have been there all night discharging my responsibilities with honour.

The following evening, I bring a big black metal police torch for cracking ghost heads and a large bottle of Jack Daniel’s for emotional support. The plan works: the more I drink, the less terrified I am. My cowardly, drunken approach gets me through, but I experience no pride. There has been no personal growth.

If I had faced my fears I might have become accustomed to the place, strengthened my character and built up my haunted-house bravery. I could have gained an ability not many people have. Instead I let fear, weakness, Cripplegate and, to a lesser extent, Christopher Walken win.

HOW FEAR WORKS

In 2022 I reached out via email to senior research fellow Dr Andrea Reinecke from the Department of Psychiatry at the University of Oxford and asked her what fear is. She told me it’s

'the physiological and psychological response to a currently present threat stimulus, which initiates behavioural strategies that will protect us from getting harmed. As an example, an angry-looking large dog running towards us will trigger a fear reaction where we step aside. Anxiety is related to worries about imagined events or events in the future.' — email interview, 19 July 2002

Remember the amygdala? The small, almond-shaped structure located deep within the temporal lobe of our brain, that’s associated with anger.It’s also in the terror business. When a threat is detected, the amygdala triggers a fear response. Our bodies undergo near-instantaneous physical reactions designed to help us get away from a potential hazard. These include physiological changes like the release of stress hormones, as well as behaviours like freezing or fleeing. Our breathing becomes shallow and speeds up, our heart races, we jump and we flinch. Interestingly, the amygdala receives input not only from our eyes, ears and our sense of touch, but also from higher cognitive centres. So we can be fearful both of actual things and of things we imagine.

A Life Less Punishing by Matt Heath (Allen & Unwin NZ, $37.99) is available in all good bookstores now.