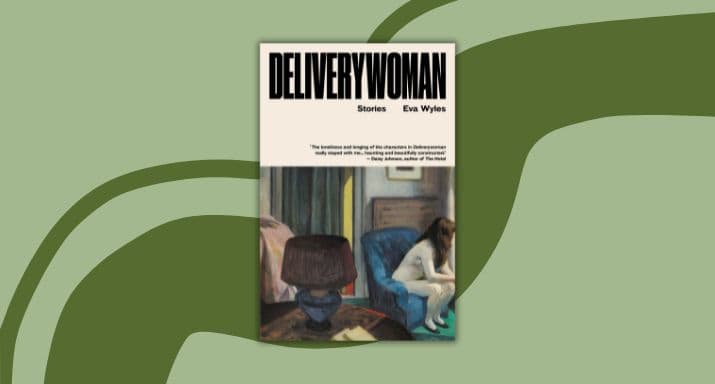

Extract: Deliverywoman, by Eva Wyles

Deliverywoman is the stunning debut collection from Eva Wyles – thirteen short stories that dive into the complexities of human connection, the pursuit of meaning, and modern-day loneliness.

Across a diverse cast of characters – from teachers and gas station workers to hedonistic revellers and wealthy gamers – Wyles explores the strange dimensions of our world and the dangers of ordinary life, with needle-sharp writing both real and surreal.

Extracted from Deliverywoman by Eva Wyles. RRP 39.99. Published by Influx Press (April 2025).

MOTHER AND

‘Time I went,’ uttered the woman, then paused to look over her shoulder. The old man had been there since she’d arrived, on the opposite end of the pontoon, looking towards the blue horizon with his legs half sunk in the sea. They had never met before, but despite this, had enjoyed, or so she hoped, a few moments of boundless peace with one another. The woman spoke again. ‘Have a funeral to attend,’ she said.

When no response was given, she used her hands to lift her bottom off the wet wood and plonk her body underwater. Then she was underwater with her eyes closed. Then she was above water with her eyes open. Then she was on the shore, looking back at the man. The woman thought about yelling across the ocean between them, something like ‘only trying to make conversation!’ but then wondered whether he may be deaf, or grieving, or anything else that would excuse him of being rude and give the label over to her instead. Lifting a towel above her waist, the woman began to both undress and dress, so that only her feet remained bare while she zig-zagged up the path back home.

Her husband was sitting at the dining table when she arrived. Her son was leaning on the porch steps, lacing up his shoes. The old man was still on the pontoon, but the distance had taken his age away and left him with only a silhouette. The woman brushed her feet off, shedding sand, and laughed. She had learnt – over the years – to laugh at herself before others got the chance.

‘Talking to strangers again?’ said her son.

‘Hardly.’ She sat down on the step with him and sighed.

‘Sighing again,’ he said.

‘And why is it that you think I’m sighing all the time?’

The son sighed too. ‘Because of your expectations,’ he replied. Behind them, her husband sighed himself, before typing something out on his keyboard. The woman raised her eyebrows. Her son went on. ‘The whole world is filled with people expecting some kind of moment to appear. Which it never does. Or if it does, they expect another after that. Hence disappointment. Hence sighing.’ He stretched out so that his feet dangled off the final step. ‘You talk to strangers in case something great might happen.’

‘I talk to strangers to be friendly.’

‘But what are you hoping to get from being friendly?’

The woman leant over and fondly tousled his hair. ‘The world does not always work that way.’

The boy shrugged her away and began to reorganise his curls. ‘It does,’ he replied. ‘You just need to answer honestly.’

When he had researched, analysed, and decided upon the rules of the world, she did not know.

He looked out across the bay. ‘What time is Mary’s service?’

The woman checked her watch. ‘Ten minutes. Will you still join? We could go for a swim afterwards.’

‘You just went swimming,’ he stated, and stood up, revealing his long almost-hairy legs. ‘Okay,’ he said. ‘But I have to go see Josh afterwards, so no swim.’

A row of heads bobbed on the screen. Some had familiar haircuts, a bush of red pinned together that the woman knew well, while others could just as well have belonged to the bodies of people she might pass on a busy street, or aboard a bus. There was a chorus of hushed whispers, and every so often, the pastor testing the microphone. It was a church neither of them had set foot in before, and the woman found herself looking for details so as to build an image in her head that she could sit in – a line of four mosaiced windows, a small wooden stage with a lectern, two stands with vases holding plastic bouquets, a sloped ceiling with a hanging projector displaying images of Mary, and what appeared to be a young IT assistant, perched at the piano bench, bent over and untangling a thick coil of wires.

The son lightly elbowed the woman. ‘It’s you,’ he said.

He was right. On the projector was a photograph of Mary and three others, the woman included, in their swimsuits and caps on the nearby wharf, with their wide happy legs poised to jump.

‘Oh, it used to be so cold,’ the woman began. ‘But we did it—’

‘Every week,’ the son finished.

The image slid away and was replaced by another – this one showing Mary in bed, connected to an array of machines, smiling and holding a newborn baby, her nephew, up for the camera to see. Feet on wooden steps came through the computer speaker, and there was a light hush as the audience quietened.

‘We are here today to show our love and support for Mary’s friends and family,’ the pastor began. ‘Who loved her so dearly through her life, and will continue to do so, even now that she is no longer with us.’

The woman could not help but train her eyes on the IT assistant. Still seated at the piano bench, small patches of sweat had begun to darken his grey shirt at the join, and his own eyes, barely visible through the screen, appeared to be darting between the wires and the projector screen, where a black line had made its way across the images.

‘I will keep this short as family and friends intend to share their personal stories of times with Mary. Gus, Mary’s husband, will speak first, followed by Jean, Mary’s twin sister, and then Pauline, Mary’s closest friend. What I would like to say, in brief, is a note on grief.’

The IT assistant dragged a spindly hand through his hair as the black line flashed and the projector went completely blank. Mary’s sister, a tall woman, made her way to where he was seated, and began to speak behind a closed hand while he nodded profusely.

‘What’s happening?’ the son said, and the woman lightly lifted her shoulders before dropping them back down again.

‘Today and tomorrow and the day after that, you will grieve the loss of Mary,’ the pastor continued. ‘And learn to live a life without Mary – from whom I’ve learnt, was a ray of sunshine in your lives. Your hearts will draw together and extend in what is to come, in a way you never thought possible, for the human heart knows no bounds to pain, and we see it break and carry on through our own living lives, limitlessly.’

Mary’s sister was bent down, her own arms inside the bundle of wires now.

‘In the coming times, remember Mary for the good that she brought you. The sort of good that is complicated, I’m sure, in the way all humans are. But, in the face of all that grief, remember how magical it can be to meet another human and hold space in your hearts for one another. That does not need to go away now that Mary is no longer here. She can still live in your hearts.’

Mary’s sister rammed a plug into a socket, and the images returned, this one showing an image of Mary and what had been her toddler at the time, standing on the shore’s edge with a small wave collapsing against their ankles.

The woman and the son listened in silence as different people ascended and descended the stage to speak. Some spoke directly to the audience while others lowered their heads in the direction of notes. Every so often, the woman sniffed her nose, or stretched her hand out and ran it down her thigh.

When the service was over and the in-person attendees were invited to move into the reception room for afternoon tea, the woman and the son remained seated. They watched in resolute silence as people stood and milled about, hugging, and then as the clusters eventually moved away, the son stood. The woman looked up at him, how tall he’d gotten, and then stood too. He leant down and put his arms around her. ‘That was beautiful, Mum,’ he said, and as their hug withdrew, he put his hand on her shoulder and gave it a light squeeze.

The old man was nowhere to be seen when she returned to the beach. School kids circled the pontoon, taking turns climbing aboard and jumping off. The woman took her shirt off and waded in. Once she was halfway submerged, she was able to make out the wharf where they used to jump off with Mary the previous year. The woman had not been there since that Summer. At the pontoon, she did not talk, nor did she climb the ladder and sit, but instead swam around it and returned to shore.

She did not know why she returned to the home office after her second swim. To her muted surprise, she had forgotten to exit the window and the service was still being streamed, only the guests had long departed, leaving behind a single cleaner, who looked remarkably similar to the IT assistant, only older, tugging a vacuum cleaner around the floor with a long winding cord. The woman also did not know why she sat back down and watched as the cleaner moved between his tasks: unpinning photographs of Mary from the cork board, collecting discarded Funeral Programmes, stacking seats, clearing the stage, taking out the rubbish bags. He was consistent with his speed, quiet in his gestures, and not once did he make eye contact with the screen. Twenty, thirty, forty minutes passed. Sounds of the husband departing floated in – a clearing of plates, a closing of his own laptop, a goodbye call. Outside, the gate clicked closed. A rubbish truck lifted bottles into its bowels and let the glass smash. The woman watched as the cleaner pressed his foot down on the vacuum and the cord shot back inside the barrel, wheeling it out of view, leaving behind the emptied church, stripped of evidence from the previous service and ready for the next.

Deliverywoman by Eva Wyles is available in bookstores now.