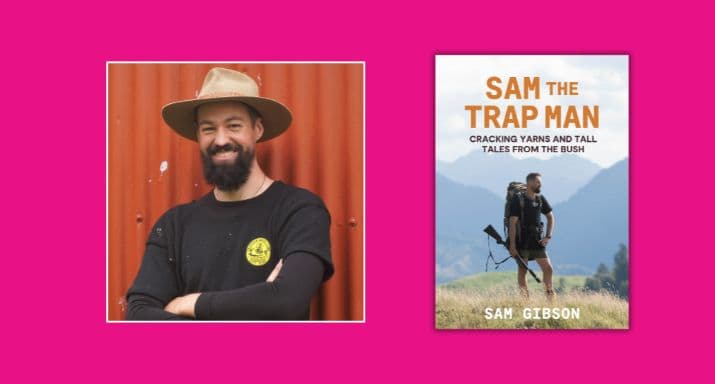

Extract: Sam the Trap Man, by Sam Gibson

Sam Gibson, aka Sam the Trap Man, is a bushman through and through: hunting, fishing, trapping and adventuring - he does it all. As an unruly teenager starting to get into mischief Sam's parents and teachers struck an unusual deal, letting him take time out of school to spend it in the outdoors, a path which would first steer him away from trouble and eventually come to define his life.

In a series of cracking yarns about his life spent in the bush - which are by turns funny, thrilling, astonishing and touching - Sam tells the story of his life so far.

Extracted from Sam the Trap Man by Sam Gibson, published by Allen & Unwin NZ, RRP $45.00.

MY START IN TE UREWERA

As I sat there munching on a kareao vine, it crossed my mind that this was a whole lot more interesting than school. Wet and hungry, I’d found myself in the heart of Te Urewera, Waimana Valley to be precise, a place where the river was still the main road, where men on horseback deterred outsiders from entering the valley (sometimes by brandishing rifles) and where wealth was measured in horses rather than cash.

I’d been sent here by people who cared about me. It wasn’t that I was doing badly at school; I was twelve years old, too early to be really mischief but old enough to be distracted, and I was getting caught up in the bogan, drug-fuelled surf scene that was rife in the coastal village of Haumoana in the early 2000s. My parents and teachers were getting a little worried, so a plan was hatched. The headmaster and my dad knew I needed a change of scene if I was to get through the next few years unscathed and I wasn’t going to get that in Haumoana.

My boss for the day was an old-timer called Keith. Keith wore black tracksuit pants, a black woollen T-shirt and no shoes. The machete in his hand was discarded for eating and sleeping but the rest of the time it stayed grasped loosely in his gnarled, arthritis-riddled fingers. Keith was softly spoken and the fact that he never smiled meant the first time I found out he had no teeth was when I cooked him steak for breakfast. He spent a good hour gumming it to death before it finally softened enough to swallow. Keith was tall and gangly, his eyes grey and glazed over like one of the old tuna (eels) in the creeks that found food by scent rather than vision.

Keith was a real bushman. A veteran of the Korean War, he once told me if you ever wanted to shoot down a helicopter, you could do it with one bullet straight through the rotor head. He started his day at 4 a.m. with a head torch, as that was when the bush was still and calm, the time it was most spiritually alive and Keith could speak with the tīpuna.

While working for Keith you didn’t take food or water with you on the hill as there would be no lunch breaks. According to Keith, when we look after the ngahere as trappers, the ngahere looks after us. This relationship with the bush just seems to make sense in Te Urewera. When we were thirsty a stream would appear, when we were hungry there was fruit on the ground or tasty kareao shoots to tide us over. Somehow there was always meat, too: deer shot in the creeks or the time Keith managed to get a slow pig with his machete. We were playing our role in the ecosystem by trapping introduced predators and in return the bush around us was abundant and bountiful. Well, that’s how Keith saw it anyway and, as I learned while stumbling along behind him as a young fella, I was inclined to agree.

Waimana Valley at the time was what the Department of Conservation called a ‘mainland island’. Its focus was on breeding kōkako and learning more about this species. Kōkako are very sensitive birds which are easily predated on by rats, stoats and possums. Ever since the time Kōkako brought Māui a drink from the stream when he was parched and exhausted from slowing down the sun, kōkako have been rewarded with the tastiest fruits from the bush.

These days their reward is more of a curse than a blessing as many of our fruiting species are being quickly eaten by possums, rats and deer. Kōkako, when they aren’t being eaten by predators, are slowly going hungry. But Te Urewera has long been a sparkling glimmer of hope among the forests of the North Island. As a teenager, I was regularly sent out to help with establishing rat and stoat traps around the last remaining kōkako in Te Urewera. This deal, struck between my concerned parents, my open-minded principal, my godfather Darren, who worked for DOC, and me is what got me through my teenage years.

I’d started going bush as a twelve-year-old during school holidays or on the weekend with Darren, mostly because I enjoyed it. As I grew older and the party scene started to sink its barbed hooks into me, my relationship with the bush grew into something absolutely vital to keeping me afloat.

Each morning we would wake up — or in my case, be woken up — and just in front of the hut veranda would be a kōkako doing its thing, singing from the top of its lungs. Kōkako are the tree monkeys of the Aotearoa bush. During the day they bounce around from tree to tree eating only the most lolly-like fruit. They are a slender bird, full of energy and fun. But in the morning when the billowing clouds of mist roll through the sleepy Te Urewera landscape, the kōkako settle down on their branches to create song. These fun-loving creatures have a deep, mournful side to them, a sad song full of lament, one of the most beautiful sounds one can bear witness to. Before singing, the kōkako sits, settles itself and quietly gulps mouthfuls of air. It puffs itself up like a balloon to what seems like triple its normal size. Out pounds this deep, rich, church-organ-like sound as the kōkako releases each gasp of breath from its lungs. It’s incredible to witness, and I’m grateful to have heard and seen it at such a formative age.

Sam the Trap Man is available in all good bookstores now.