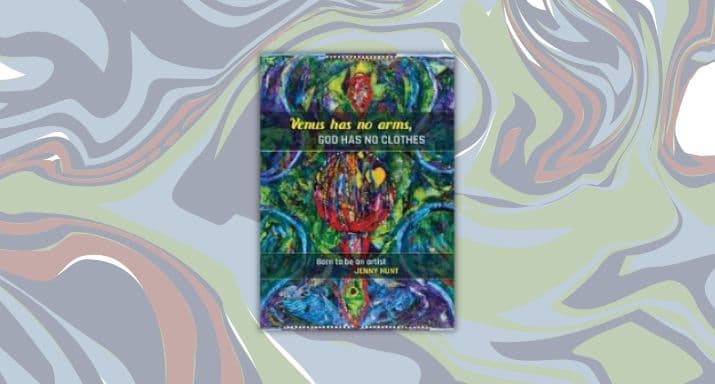

Extract: Venus Has No Arms, God Has No Clothes, by Jenny Hunt

Jenny Hunt grew up in Hawera, Taranaki, in the 1940s and '50s, with four siblings and parents from widely different social milieus. Her mother's family moved in the upper echelons of Auckland society until they lost their fortune in the Great Depression, while her working-class father was a direct descendant of a Chickasaw Native American sentenced to penal time in Australia.

Venus Has No Arms, God Has No Clothes is a moving and detailed portrait of the childhood of a prolific New Zealand artist, evoking the conservatism of the era she grew up in and the obstacles she had to battle to realise her vocation.

Extracted from Venus Has No Arms, God Has No Clothes: Born to Be an Artist, by Jenny Hunt, published by Atanui Press. $45.00

On the twenty-second of January 1956, I turned seventeen. I was staying in Hāwera, helping to look after four small children I had minded before we left there, while their parents worked. Ten pounds was to be my payment, which would set me up very well for beginning my final year at school.

On that same day, I received my School Certificate results. I passed by twenty-two marks. Better than anyone had expected. In my eyes, my status as a trainee artist had been recognised and I could return to school as a sixth former, to do the preliminary art subjects which were required to become a fine arts student. I was flooded with relief and a little private vindication.

Congratulations on my return home to Auckland were low key, not what I had been anticipating. After a school career of substandard reports which praised only my art, English and biology ability, I felt proud that now, when it really counted, I had delivered. Academic achievement had always been held in the highest regard by my mother, but as I was to find, only in certain subjects. Her subjects.

‘Yes,’ said my mother, ‘you have quite good marks for art and biology, but that just goes to show

that if you can do well with those subjects then you can also do it with history, and geography.’

That statement planted a deep fear in me that a battle I thought I had won was about to be resurrected and I was not wrong. I had always had an uneasy feeling that my mother perceived my commitment to art as not genuine but an act of defiance against her, undertaken at my peril.

With great care and being as adult as I could, I replied, ‘Well, I really did try for three years and as you know failed except for art, English and biology. Drawing and painting have always been what I am best at. They are things I understand, and I think I could do well at sixth form art.’

‘We’ll see,’ said my mother, tossing her head in what I could only interpret as a danger signal. ‘Academic subjects are always more important.’

When school started a few days later, the matter was still unresolved. My mother wanted to know what the teachers thought, so a consultation with the headmistress was arranged. On the day, I waited for my mother at the school gate, feeling excited and important because my future was going to be discussed at the highest level. Miss Reece, the art teacher was supportive, Miss Gardner the headmistress was encouraging, and I was confident that my mother would respect their opinions as fellow academics.

The carpet in the headmistress’s office was shabby. Sun shining through high windows highlighted

threadbare areas. Miss Gardner, bustling and welcoming, greeted my mother then they both sat down

while I remained standing.

‘Jennifer did very well last year,’ began Miss Gardner. ‘Her marks in biology were the highest throughout the fifth form but Miss Reece and I both feel that her true vocation lies in art.’

I smiled and gave a small nod to Miss Gardner. Her words were balm to my soul. I waited for the beautiful words that would seal my fate. They didn’t come.

Looking at my mother, I could see immediately that she had taken exception to the headmistress’s words, by expressing an opinion that she did not share.

For this reason, and this reason only, my mother, adopting an imperious tone made the following statements.

‘I do not consider art to be a true academic subject so my preference is that Jennifer replace art with history and geography and once she has mastered those, perhaps we can look at art again if she is still interested.’

‘Besides,’ she added, in her haughtiest voice, ‘Jennifer can already draw and paint very nicely.’

In that second, my world totally disintegrated. My feet began to dissolve into the threadbare carpet, and I grasped the corner of Miss Gardner’s desk so that I could remain upright.

For the next two days I was unable to speak, or cry or eat. On the third day, at the bus stop, attempting to return to school, I put my foot into the bus, was immediately overwhelmed with dizziness, stepped backwards into the bus shelter and fainted.

Next day, at school, I sat through an English class, comprehending nothing. Then came a double period of history. I sat at the back, trying to bring my mind under control and concentrate on the lesson. A sensation of coldness in my brain frightened me and that quickly turned into a feeling of overpowering dread that something horrendous was about to happen. I ran towards the door, between rows of desks, past the teacher, out into the hall.

This became a repeating pattern, having to get out of classrooms, unable to explain why except that I felt unwell. Teachers became angry with this behavior and with my erratic attendance. There were days when I had to get off the bus in a state of panic then wander around in an unknown place until I felt able to get another bus, either to school or home.

My mother assumed I was doing a big dramatic sulk because I had not got my own way. She had no idea what she had condemned me to and I was worn out trying to change a mind that had no intention of changing. All I could say to her was that I could no longer deal with being at school if I could not study art and I wanted to leave.

‘You are exaggerating the situation,’ she said, annoyed. ‘I made the decision for your own good. You can paint and draw any time and you have proved that you can get good marks, so I don’t want to hear any more about it.’

‘I am not a child now,’ I replied firmly. ‘I do not have the same interest in these subjects that you do, and they will not be of use to me when I become an artist which I intend to do. It is just a waste of time as far as I am concerned.’

How, I wondered, could she insist on me carrying on with what had become a ridiculous farce in which I knew I could not survive much longer.

I decided that I could only endure the first term if I knew I would leave at the end of it. However, I could not even manage that. Repeated episodes of claustrophobia and panic attacks soon made it impossible to travel on the bus.

Even going outside became difficult. The sun, or just the light was suddenly too strong for my eyes. My ears were ringing, I had no appetite, drawing and painting did not help me and in fact they seemed to have become my enemies.

My mother was teaching so she and the rest of the family all left early in the mornings. I stayed in bed until they were gone and returned to bed when they started arriving home. Playing the piano was the only thing I could do to block out the ringing in my ears, so I played all day. No one in the family knew what to say to me and I had nothing to say to them.

The doctor came and tapped my chest and back.

‘Does that hurt?’ he asked after each tap. When he got to the upper back, I said, ‘Yes, that hurts.’

The pain really seemed to come from my chest.

‘Just my heart broken again,’ I said to myself.

Then the doctor said, ‘Jennifer, are you worried about anything, is there something on your mind

you would like to talk about?’

What was he saying? No one had ever asked me if I was worried or even mentioned my mind before, so I certainly did not know how to answer that one.

‘No,’ I said, ‘I don’t think so.’

Various people were brought in to talk to me, not to listen to me. They all began by saying that what my mother had done was for my own good and then went on to tell me how selfish, unnecessary, and useless artists were. I didn’t listen to them, I couldn’t. My mind was totally engaged in the problem of persuading my mother that I must leave school.

Venus Has No Arms, God Has No Clothes is available in bookstores now.