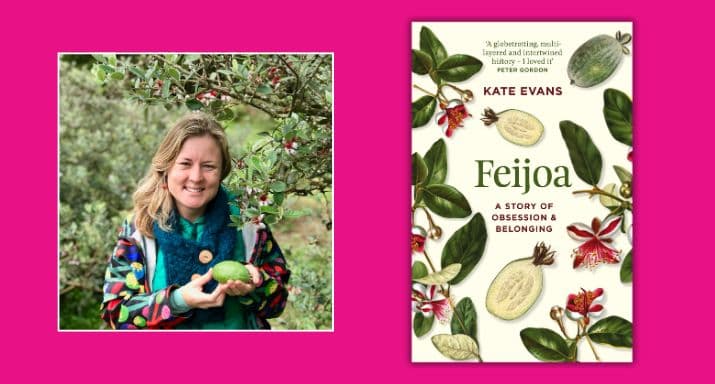

Extract: Feijoa, by Kate Evans

Author Image Credit: Omar Quintero

Inspired by a personal obsession with this singular exotic fruit, Feijoa is a sweeping, global tale about the dance between people and plants – how we need each other, how we change each other, and the surprising ways certain species make their way into our imaginations, our stomachs, and our hearts.

The feijoa comes from the highlands of Southern Brazil and the valleys of Uruguay, where it was woven into indigenous and Afro-Brazilian cultures. It was scientifically named in Berlin, acclimatised on the French Riviera, and failed to make its fortune in California. Today, it is celebrated by one small town in the Colombian Andes, and has become an icon of community and nationhood in New Zealand.

Feijoa is a book about connection. Between people and plants, between individuals, between cultures, across disciplines – it celebrates the ways our lives and loves intersect in surprising ways.

Extracted from Feijoa by Kate Evans, published by Moa Press, RRP $39.99.

We were driving back to Cannes when all at once I saw a familiar house out of the window. It was the one Florence’s friend Nadine had photographed twenty years earlier, thinking it could be Villa Colombia. Paul stopped the car and I hopped out, jumping up on a low wall to peek at the house. It had the same rectangular profile and rows of three shuttered windows, but no balconies, and the orientation to the road wasn’t right. Then I noticed a slight woman around Florence’s age sitting in the garden watching me as I balanced on her fence. She came to the gate, Florence explained our story, and the woman invited us in. Her name was Ghislaine, and this couldn’t be Villa Colombia, she said – her own grandfather had built the place in 1912.

But when Florence mentioned Villa Endymion, she brightened. ‘That’s just up the road!’ she said. ‘Do you want me to take you?’ Hardly daring to hope, we followed her back along the street the way we had come, past some bizarre mobile phone towers poorly disguised as metal conifers and Phoenix palms: ‘The whole neighbourhood opposes them,’ said Ghislaine. When she was a child, her father had worked as a gardener at villas all around Golfe-Juan, she said, and he used to bring home feijoas for her. ‘It’s like a little kiwi, you cut it open?’ This suburb was called ‘Little Africa’ at the turn of the twentieth century, she said, because of its warm microclimate and exotic gardens.

Up ahead was a large black metal gate, decorated with gold curlicues and set diagonally across the corner of the avenue and a small street. Beside it was a little plaque reading ‘Villa Endymion’. ‘Et voilà,’ said Ghislaine. Behind the gate towered (real) palms and cypresses, and nestled among them was a peach-coloured rectangular house with rows of three shuttered windows . . . I ran down the street towards it, and there, on the wall near another gate, a creeper climbed over a hand- painted tile: ‘Villa Diane’.

Looking up, the house had the same scalloped balconies and Grecian columns as the photographs from the real estate file. Florence and I excitedly looked from the historic pictures to the house in front of us. It was clear this really was André’s original Villa Colombia. While we were talking, the large gate up ahead began to open, revealing a mass of greenery beyond. A fit blond man in his fifties waved a visiting car out of the driveway. He had striking light blue eyes, and looked somehow familiar. (I realised later he reminded me of James Bond actor Daniel Craig.)

I ran over to him, and began a breathless and mangled French explanation of our mission. I called Florence over to help. The man’s name was Brice, she translated, and he looked after the garden year-round for the wealthy, often-absent British owners. Yes, he said, there are still feijoas here. ‘Come, I’ll show you.’ He set off briskly up the tidy stone path with his golden Labrador trotting behind. Ghislaine waved and walked home, but Florence, Paul and I followed Brice into André’s garden.

———

The original property had been divided in two, Brice said. Villa Diane, the original Villa Colombia, belonged to someone else, while his bosses owned the newer Villa Endymion and the majority of the garden. It wasn’t always this neat. Brice started working here seventeen years ago – after serving in the French military in Africa, he had been searching for a more peaceful life. Back then, he said, the garden was a jungle, and it’d been his job to restore it. When the owners learned about André, they asked Brice to try to re-create the original garden. They even asked him to replace all the newer concrete paths with the original stone.

‘Here’s a eucalyptus your ancestor planted,’ Brice said to Florence. ‘It got hit by lightning five years ago, but it’s growing again.’ He pointed out three specimens of Gunnera tinctoria, the giant Chilean rhubarb, their massive upturned leaves a ridged topography of mountains and valleys. André planted them in the garden, too, he said, but they have become such an invasive pest that selling or propagating them in both New Zealand and the European Union is now illegal. There was a tiny Araucaria angus- tifolia, too – from the feijoa’s native forest in Brazil – which Brice said he’d bought in England and brought back by car, part of an effort to collect every Araucaria species for the garden.

Then we crossed the ravine on a little wrought-iron bridge. ‘There’s the feijoa,’ said Brice, waving. I turned back and squawked in excitement – I’d walked right past it. There it was indeed, blending into a wall of green on the uphill side of the bridge. I could see immediately, though, that this was no ancient grand- mother feijoa. ‘Is this

the biggest one?’ I asked. It was. There had been another one here, Brice said, but it had gotten sick, so they had cut it out in case it contaminated other trees.

‘It has the most magnificent flower, so delicate!’ he said. It only fruits every three years or so, and Brice hadn’t tasted one, yet. But when it’s windy, he said, the shaking branches reveal the undersides of the leaves, so they flash dark green and silver. ‘That attracts the birds that pollinate it – isn’t it genius?’ I’d never heard that theory before, but it could be true. Birds are highly visual, after all.

I hadn’t found André’s original feijoa, but this was probably one of its children or grandchildren. Perhaps, on this very spot, André knelt in the soil and pressed his layered feijoa into the ground, or stood here to make the observations of the plant for his article in the Revue Horticole. I paused on the little bridge while the others went

on ahead among beds of fragrant Provençal lavender. The mature trees, the feijoa, even the recurring weeds – they all bore André’s imprint. On these few hectares of earth, he carried out his experiments and ate his first feijoa.

Eleanor Byrne, analysing what she calls the ‘postcolonial gothic’ in Jamaica Kincaid’s work, writes that all gardens are haunted – that almost every garden must be made from the ruins of the one that preceded it. ‘[T]races of others’ lives still remain deep in the soil, that may reveal themselves, uncannily, not uninvited guests to the property, not invaders, but ghosts . . . introduced to the garden by other owners and gardeners, whose legacy must be reckoned with.’

I liked the idea of botanical ghosts, wriggling up through the earth after decades of dormancy, telling a subtle story of the people, like André, who had once gardened this same soil. Brice led us around the corner towards the main house: the Villa Endymion, which had been built after the André brothers sold the property, on the site of the half-moon observation terrace where Florence’s elegant aunts had strolled in 1908. It was still there, the semicircle deck just incorporated into the main house. Now, it overlooked a mature Chilean monkey puzzle tree (first cousin to Brazil’s araucarias) and an inviting, crystal-clear infinity pool.

‘Oh là là, all of this is very moving.’ Florence was ebullient, her tiredness forgotten. ‘I love seeing all this, it’s incredible,’ she said to Brice. ‘How extraordinary that you opened the gate exactly at that moment. You can’t imagine what it means for me to be here with you. When I think that my father played here as a child!’ Until today, she had thought that Villa Colombia had been developed beyond all recognition, like so much of this glamorous coast. Then, for a brief moment, we had feared it had been mistreated and abandoned. But now, here was her patrimony, her ancestor’s garden, still an oasis, uncovered by concrete, a living record of the exotic plants André had loved.

Looking back at the real estate map, it seemed clear that the roads had been mislabelled, or else the names had changed. Avenue Édith Joseph followed the same contours around the hillside and ravine, but was located a few hundred metres further down the slope than the actual street that curved around André’s garden. Somehow, miraculously, we’d managed to find Villa Colombia anyway.

Feijoa is available in all good bookstores now.