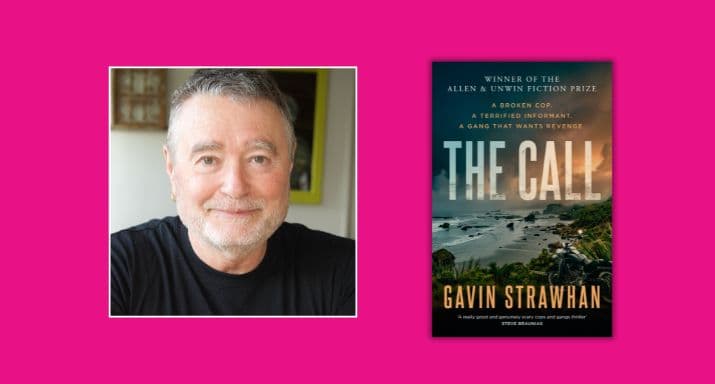

Extract: The Call, by Gavin Strawhan

Photo Credit A McNutt

After surviving a brutal attack, Auckland cop DS Honey Chalmers has returned to her hometown to care for her mother. The remote coastal settlement of Waitutū holds complicated memories for Honey, not least the tragic suicide of her younger sister, Scarlett.

Honey is hardest on herself. She let herself get too close to a gang informant. She got sloppy. The Reapers are a 501 gang of Aussie imports, ruthless and organised, and she's pretty sure the informant, mother-of-three Kloe Kovich, paid the price. But when a couple of gang enforcers turn up in Waitutū, Honey realises they are hoping she will lead them to Kloe. But if Kloe is still alive, can Honey save her this time around?

Gripping and suspenseful, with a killer ending, The Call propels the reader into the world of a terrifying new kind of gang – and introduces a major new talent in crime writing.

Extracted from The Call by Gavin Strawhan, published by Allen & Unwin NZ, RRP: $36.99

THE 10K RUN AROUND THE town and along the beach had been fine, the decision to tackle the summit track at full tilt not so much. Lungs burning, hunched over her knees, she forced herself to stand, and raise her freckled arms to the flat grey sky. A bull at a gate, her mother was fond of saying. Under an oversized tee and flannel shorts, she felt the puckered flesh around her spine resisting, tugging at her skin, as her lungs tried to expand. She pursed her lips, slowing her breath, distracting herself with the view from the rocky heads, around the graceful curve of the deserted sandy beach, and down to the pale shards of sandstone of the sheer cliffs at the other end of the bay. Views from the first seventeen years of Honey’s life.

Skinny, eight years old, mandarin curls in a saggy bucket hat, out in the bay in her father’s old boat, pulling in snapper and gurnard by the bucketful. Building sandcastles, running races, swimming and boogie boarding, making best friends forever in the few weeks over summer as the camping ground filled up. Friends to be replaced year after year until she learned better. Lonely, misunderstood tweens. Squatting on an oyster-studded rock, watching translucent crabs cautiously emerge, imagining she knew how they felt.

A first kiss over there, first heavy petting there, first actual sex, clumsy and embarrassing in a battered black Nissan parked by the boat ramp. Down there, also, the bench seat on the little strip of green before the beach, where her mother had taken her and her sister the day their father didn’t come home. Fourteen years old, running to the beach, furious after seeing their mother flirting with the weekend fishermen at the golf club, all cleavage and lipstick, so obvious. And then the other, darker thoughts — the kind the counsellor wanted her to deal with.

Bugger it.

Honey willed her body into motion again and ploughed down the track, jumping patches of sand tussock and pigface in pink flower, then on to the beach again and away.

‘HEY MUM!’ HONEY CAME IN the back door, gulping the last of the water from her bottle.

‘I’m back,’ she added unnecessarily.

Still nothing. An irritating whisper of concern. Would she ever be able to walk into a house and it just be walking into a fucking house for chrissake. She placed her bottle down on the kitchen counter and padded down the passage to the living room. Rachel was stock-still, staring at a pad of Post-it notes, a pen in her left hand.

‘Mum?’

‘What’s it called? That thing. That you put the magazines on?’

‘The coffee table?’

‘Yes, the bloody coffee table.’ She typed it into her mobile phone. ‘Also known as kāfēi zhuō.’ This in a faux singsong accent. Vaguely racist but what was the point. Honey watched her mother carefully write down both versions and stick the Post-it to the edge of the coffee table.

Rachel’s white hair, recently thick and naturally dark, was the texture of dry grass. Her face was lined, deeply etched, her hands too, the crinkle-cut skin of a lifelong smoker. Ironic.

Rachel had been a lifelong health worker, a community nurse in a community that still revered her, even after her forced retirement. She’d been in decline for some time, but nobody had wanted to admit it, least of all Rachel herself. Oh, she’d felt a bit rocky, she’d concede, ever since Ron passed. He’d been a weekend fisherman who ended up staying nearly twenty years before a series of strokes stole away his speech, his mobility and finally his life.

Nearly every family in the district owed Rachel some debt, had stories of how she had helped them or their loved ones. She lunched with the mayor, harassed the regional health board, was quoted regularly in the Bay Advocate, provoked immunisation drives, was a sharp-tongued advocate for those who needed it. In the end, it was Wiremu from the garage who rang Honey to say that something needed to be done.

Ti-i-ming.

Honey was convalescing after the incident. She reassured Wiremu that she’d sort a few things and drive up to Waitutū as soon as she was able. But the moment she put down the phone she had to fight the urge to cry, though it was hard to tell if it was for her mother or for herself. Funny, considering she hadn’t cried during or after the beating that had nearly killed her. Apparently, fists, bats and knives had nothing on her mother when it came to making her feel inadequate.

‘She’s an amazing woman, your mum,’ was the first thing Wiremu said when Honey pulled in to fill her Mini Clubman and do some preliminary reconnaissance.

Wiremu’s garage had been there from the beginning of time: two pumps, a shop that sold everything from bait to bread, and an attached workshop. He’d come waddling out as she was still unfolding herself. It was only a four-hour drive from Auckland, but she’d been weaning herself off the painkillers.

‘But it was getting out of hand,’ he went on, ‘her forgetting appointments, losing stuff, denying she’d done this or that. And her temper, oh, boy, she called Henry Scott up at the school every name under the sun when he tried to persuade her to see the doc.’

‘No, that’s fine, I’m glad you called,’ she said.

‘I’m just grateful you could come, Honey. Considering everything . . .’ Wiremu let that linger like a question.

Honey just smiled and shrugged. ‘All good.’ Though of course it wasn’t.

‘Well,’ Wiremu beamed, ‘bet you’re glad to be home.’

Everyone who stayed in Waitutū thought it was the best place in the world. Everyone who disagreed got out as soon as they could. Honey had left a few days shy of her eighteenth birthday. She never regretted it. Too many ghosts, not just her sister’s, she told her counsellor, offhand, but of course that was her hoping to avoid having to go into the details. The counsellor had kept digging until Honey stopped going to appointments. And here she was anyway, back at the source.

‘Yeah, it’s great. Apart from the bit where my mother has dementia.’ She smiled wryly to show he didn’t need to tiptoe around her.

But Wiremu stiffened slightly, as if he detected some criticism lurking. ‘She’ll be pleased you’re here,’ was all he said. ‘Everyone needs their whānau with them at times like these.’

Honey really wished she could agree.

The Call is available in all good bookstores now.