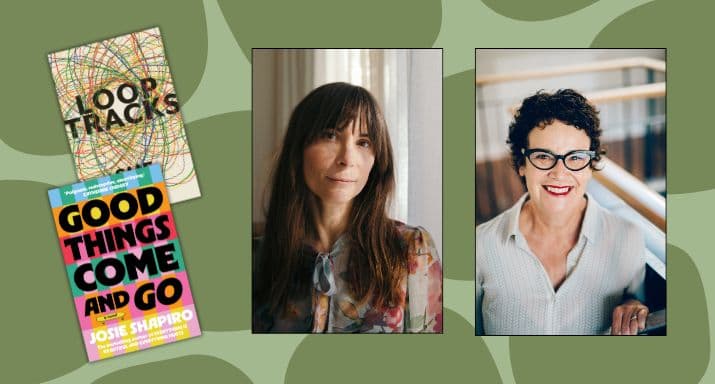

Skateboarding and research joy: Josie Shapiro and Sue Orr

Kete chased down two fabulous authors, Josie Shapiro (author of recently released bestseller Good Things Come and Go) and Sue Orr (author of Ockham-longlisted Loop Tracks), to chat about skateboarding, the joys of research, and puzzling characters. Read on for their conversation!

Author photos credit Ebony Lamb

Sue: I had such a good time diving into Good Things Come and Go Josie. I couldn't put it down, and finished it in one glorious sitting. Where did come from? What was the genesis of the story?

Josie: The idea for the story came from watching my daughter Marnie at an after-school skateboarding class. She started when she was six, and I had to admit some apprehension when I got there: a bunch of young guys with very baggy trousers who looked more at ease skating than teaching young kids. But my stereotyping was hasty, because alongside their risk taking and their counterculture attitudes, these young men were impressive. Gentle, careful, and patient. Within the first lesson my daughter learned to skate along safely and over the coming months they taught her to do a few tricks and drop into ramps. I was mesmerised by the skills of the young men on their boards too, how they were both athletic and balletic, and when I considered the time it takes to learn these things, as well as the resilience required to continue trying after so much failure, I could feel my two characters Jamie and Riggs begin to coalesce. I was interested in the challenge of describing with language the way they moved on their boards and the complex nature of being skateboarders but also sensitive, thoughtful young men. And because I love the structure of a triangle, the uncertainty and strangeness of the shape, I thought about including a love triangle, and that is where my character Penny Whittaker came in. So, it was interest in an obsession with skateboarding, and then from there it was definitely character driven. Do your stories and novels come from character or from idea or perhaps one clear scene, or is it like a mixture of all these things from the beginning?

Sue: It’s a mix for me, I guess — a vexed curiosity about why people (or societies) behave the way they do, especially when they take the moral high ground. But I never start writing until I’ve got an equally puzzling character taking shape in my imagination. But let’s get back to skateboarding! I was so blown away by your depiction of the skateboarding in your novel, I was convinced you had to be a skater (if that’s the right term) yourself. How did you approach the research, to get it so authentic on the page? Did you eavesdrop at that skatepark?

Josie: It’s funny when I think of the word research, as it felt so organic when I was writing that the word research never really came to mind. When I find something I'm interested in, I become sort of obsessed with understanding and learning, so it never feels like work. As I said, I went to my daughter's class and watched little kids learning the basics, and then I went and sought out as much as I could find on the internet and, yes, at skateparks, in different towns in New Zealand, just to watch and see the dynamics and how people behave there. There's a lot of skateboarding videos online too that I watched, not only old classics but also the Olympic games, the Street Skateboarding League, and also the incredible amount of teaching videos breaking down how to do certain tricks. I watched a lot of Skate Tale with Madars Apse, which I loosely based the idea of a show in the book, too. But no, I don't skate myself. Maybe some writers would have taken a few lessons, I don't know; would you have thought it necessary? How far do you go in terms of 'method acting' in your research, if that makes sense?

Sue: I agree, research is a really clinical term for the obsessions we get with the subject matter in our stories! I don't feel as though I need to 'be' my characters (as in be a method actor)... but I can imagine what their lives might be like, and the wealth of material available on line means there's no excuse not to create authentic worlds for them, that's for sure.

Josie, I was in awe of the complexity of the three main characters — Adam, Jamie and Penny. They all have their flaws, but they earn the reader's sustained empathy because you refuse to let them collapse into stereotypes. How you approach character development in your writing? Did you know their back stories before you started writing the book?

Josie: I find with character it comes to me in the writing, so I just dive into scenes that I can see (or actually a more accurate word might be 'feel'). They didn't all come at once. I knew their names, and roughly how they related to one another, but they each developed separately - Jamie arrived first, and I worked on his chapters first, then Penny, and finally Riggs, who took the longest to find a voice and a story. Some of his chapters were the very last to be written! I did find that once I understood how to make him come alive, he was a lot of fun to write. I find character is where I turn to when I find I get stuck with the plot. For example, I wrote a pretend conversation transcript for Penny and an imagined therapist, to unlock how she felt about other people in her life, and how she felt about herself, and although it was never intended for the novel itself, it gave me plenty of gristle to chew on in the text later on. I did want them all to all feel soft and hard, good and bad, thoroughly human, and I'm glad that's how it read to you. They also did plenty of things to surprise me and keep me on my toes. Does that happen to you? That you're writing and a character says or does something and it's like oh, okay, that's where this should go?

Sue: Yes, I love it when my characters surprise me! One thing I’ve taught myself to do is stop often and ask myself what are the other possibilities, in this moment, for this character? Rather than racing on to a pre-conceived moment in the story, just pausing for a moment and interrogating alternatives not immediately obvious. It’s something I’ve encouraged my creative writing students at the IIML to do too, with great results.

The relationships in your book are so intriguing, and I loved how the story was still offering up surprises at the very end. I don’t want to spoil things for your readers… but by the end I was thinking what a great feminist novel it is. Was that something you were thinking about, when you wrote it?

Josie: I'm really glad you found that energy at the end. There was a sense for me that what mattered most for Penny was that she had a story arc that was true to her deepest desires, and I wanted through her story to explore what freedom means for a woman in a world where we submit to the power and gratification of men in so many instances. And because it was a triangle relationship, with an emotional movement between all three characters, I knew Penny would be the apex, the centre of the storm in a sense, and that was on my mind to view her through a feminist lens. But although I knew how I wanted her story to feel, it still wasn't clear to me exactly how the story would tie up until very late in the drafting.

I read once - I can never remember who first said it - that the ending should feel 'surprising yet inevitable', and I also feel that there needs to be a satisfaction in some sense for the reader, especially if all the loose ends aren't fully tied up. I hope that I've come close to an ending that is open for a future of the characters beyond the novel yet feels like a resolution that makes good the pact made with the reader at the beginning of the book. I'm starting now to really think about my next project, and last night I was aware that the emotional time and energy given to these three characters over the years was the same as if they were real people, so there's a true sadness in saying goodbye and letting them go. I think the ending of this book helps give me some closure, too.

Good Things Come and Go and Loop Tracks are in bookstores now.