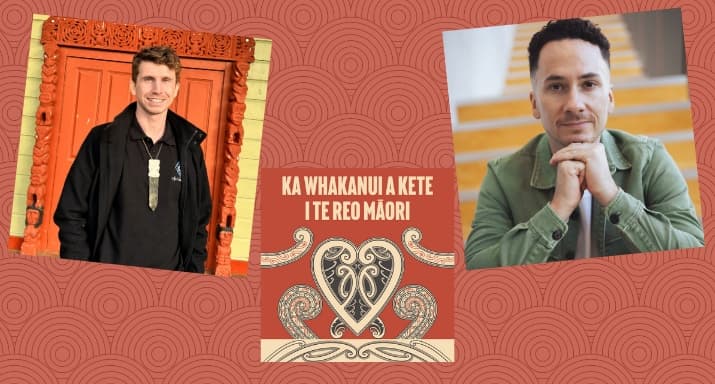

'Te reo Māori is how I speak to the world around me': Airana Ngarewa

He kaituhi, he kaiako hoki a Airana Ngarewa nō Pātea, Taranaki (ko ōna iwi, ko Ngāti Ruanui, ko Ngā Rauru, me Ngāruahine). I te rārangi o ngā pukapuka i hokona nuitia tana pukapuka tuatahi, The Bone Tree, mō ngā wiki tekau mā rua. I whakaaweawetia tana pukapuka hou, ka whakarewahia i tēnei marama, e ngā tūpuna o tōna anō iwi me ngā kōrero i tukua iho i roto i ngā reanga o tōna whānau. Ko te take o te kōrero kei Taranaki i ngā tau 1940, ā, ka whāia a Koko, he kaumātua mōrehu nō ngā pakanga whenua, nō Parihaka, nō ngā whare herehere anō i Ōtepoti, nōna ka whakatau i ngā maharatanga o mua me ngā toimahatanga o te muru. I tēnei pukapuka hou nāna, e ū tonu ana a Ngarewa ki te whakaputa i ngā kōrero nō tōna anō rohe o Taranaki, ā, i kōrero tahi māua mōna me āna mahi.

Airana Ngarewa (Ngāti Ruanui, Ngā Rauru, Ngāruahine) is a writer and educator from Pātea, Taranaki, whose debut novel The Bone Tree spent twelve weeks at the top of the New Zealand fiction bestseller list. His upcoming novel, The Last Living Cannibal, launching this month, is inspired by ancestral figures from his own history, drawing on stories passed down through generations of his whānau. Set in 1940s Taranaki, the book follows Koko, an elder who survived the land wars, Parihaka, and imprisonment in Dunedin, as he faces ghosts of the past and the demands of muru, the restoration of balance. With this new book, Ngarewa continues his dedication to telling powerful, deeply rooted Taranaki stories. I had a kōrero with him to get to know him and his work a little bit better.

Kia ora, e hoa. Tēnā, nā wai koe, nō whea hoki koe, ā, he aha hoki āu nā mahi i tēnei wā? Tell me a bit about you, who do you descend from, where do you come from, and what are you up to these days?

Nowadays, the way I tend to introduce myself is simple: My name is Airana and I’m from Pātea. Pātea is famous for the Pātea Māori Club, and I am famous for belonging to the only whānau in Pātea that never made its ranks.

I mua, he kaiwhawhai koe, ināianei, he kaituhi kē. He aha i huri ai tāu nā mahi? Kua roa koe e pai ana ki te tuhituhi, i tūpono noa rānei koe ki te mahi nei? You were a fighter, now you’re a writer. What brought on that shift? Were you always into writing, or did it sneak up on you?

In truth, the title of fighter still sits more comfortably with me than writer. Fighting was ingrained in me from a young age. My parents fought and won national titles. All four of my siblings fought and did the same. If I thought I could get away with a career in fighting and avoiding brain injury, I’m sure that’s what I would still be doing. Reading snuck up on me as I was wrapping up my career in that world, and then writing not long afterwards.

I pānuitia e au, i takoto i a koe tō kupu, ka oti i a koe ngā pukapuka e toru i roto i ngā tau e toru, ā, ko The Last Living Cannibal te tuatoru o ēnā pukapuka. Ehara i te hanga tāu mahi! He aha ngā akoranga kua mau e pā ana ki te āhua o āu mahi tuhituhi? I read that you set yourself the challenge to write three books in three years, and The Last Living Cannibal is number three. That’s pretty amazing! What did that process teach you about your writing?

I don’t overthink writing. I believe compelling writing comes from compelling people, and compelling people are shaped by compelling experiences. So I focus on doing what interests me, trusting that when I sit down to write, it will flow onto the page.

Nā, kua tutuki tāu i whai ai, nō reira, he aha kei tua? And now that you’ve pulled it off, what’s next?

Five books in five years! The fourth is already written and ready to go next year. So that just leaves one more. My first sequel.

He rawe ki a au te āhua o tāu tuhi, he rite tonu ki te āhua o tā tātou kōrero ki a tātou anō. E rongo ana au i aku whāea, aku mātua, aku koroheke me aku rūruhi i ō kupu. Nō wai ngā reo e whakaaweawe ana i ngā kiripuaki, e whakaahua ana hoki i te āhua o tāu tuhituhi? I enjoy the way you write, it’s the way we talk to each other. I can hear my aunties, uncles, koro, and nannies in your words. Whose voices inspire your characters and shape your writing style?

When I share the speaking benches with my whānau, my goal is always to be the funniest person in the room. On days I don’t get there and my whānau beat me out, I steal their jokes and put them in my books. If my writing sounds like your whānau speak, I may have just stolen their words too.

He pukapuka reorua a Pātea Boys, ā, he reo Māori kei The Bone Tree me The Last Living Cannibal. Ko te whakamahi i ngā reo e rua tāu e pai ai? Pātea Boys is fully bilingual, and te reo is in both The Bone Tree and The Last Living Cannibal. Is using both languages what feels most natural to you?

English is my lazy language. It’s what I resort to when I’m feeling tired. Te reo Māori is how I speak to the world around me, especially the birds who surround me and my whare. Neither language feels natural, though. I say instead that growing up with two big sisters, fighting is my first language.

I te pukapuka o Pātea Boys, i pēwhea tāu whakaoti i te whakamāoritanga? Nāu i mahi, nā tētahi kē atu rānei koe i āwhina? With Pātea Boys, how did you tackle the translation? Was it all you, or did you work alongside someone?

Tackle is probably the right word. I had never come close to writing tens of thousands of words in te reo Māori before. But, not a single full-length book had been written in the dialects of Taranaki this century and so it felt the right way to spend my energy after the commercial success of The Bone Tree. Perhaps it was a reminder to myself to stay grounded: that writing is bigger than book sales.

I was lucky to be guided along the way by Darryn Joseph, who had spent many years in Taranaki working alongside many of the elders who were long gone before I stepped foot into this world. If there is any turn of phrase that is clever in the book, it was likely this man’s doing.

I tupu ake koe i te reo Māori? He aha rānei te huarahi i whāia ai e koe hei ako i te reo? Did you grow up speaking te reo Māori? If not, what path did you take to learn it?

I was fortunate to grow up in a family that had already reclaimed its reo. After being kicked out of kōhanga reo at just four years old, I was content to leave it to the rest of my whānau to protect and uphold. But as the years passed and the elders grew older, that luxury disappeared. When my turn came to learn, I dove into the deep end, making myself available for every kaupapa imaginable, until the old people decided it was time to throw me on the speaking benches, and that was when the real learning began.

Ō tāua iwi, a Taranaki me Tainui, he nui ngā hononga, kei The Last Living Cannibal ētehi. Ka pēhea tō whakamahi i ō tuhinga hei waka kawe i ā tātou kōrero, i āu kōrero ake hoki nō Taranaki? Our two iwi, Taranaki and Tainui, have deep connections, some of them mentioned in The Last Living Cannibal. How do you use your writing to carry and share our histories, especially your own from Taranaki?

I don’t know what else I would be writing about if I weren’t writing about history. On the rare occasion when I have written about more contemporary events, my whānau - correctly - accuse me of writing about them. So I try to avoid that where possible. Saves the awkward whānau dinners where this person asks if they are that character and I have to pretend they aren’t.

Ngā kaituhi Māori, me aha e tautokona ai, e whakanuia ai hoki ā tātou kōrero me te hunga e tuhi ana i aua kōrero? Māori writers, what do you think needs to happen to make sure our stories, and the people telling them, are truly supported and celebrated?

I think writers should spend their energy instead on celebrating those around them. Their culture, their history and their language included.

He kupu atu anō āu mā te hunga e hiahia ana ki te tuhituhi i ā rātou ake kōrero? Any words for anyone out there who’s keen to start writing and tell their own stories?

I don’t think so. Leave the advice to men and women older and much wiser than me.

The Last Living Cannibal (Moa Press) will be published September 30. The Bone Tree and Pātea Boys are both available in bookstores now.