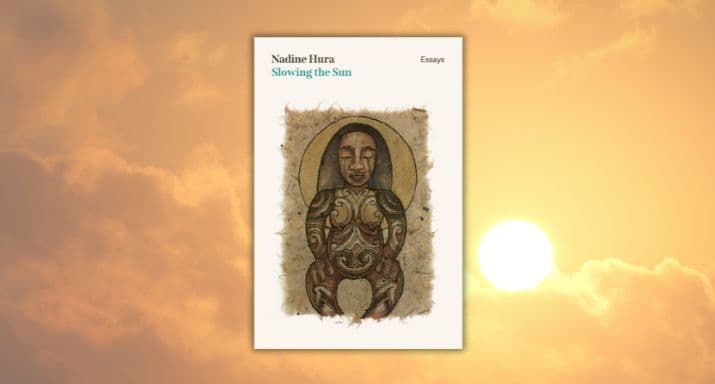

Extract: Slowing the Sun, by Nadine Hura

Hope is a shovel and will give you blisters

Overwhelmed by the complexity of climate change, Nadine Hura sets out to find a language that connects more deeply with the environmental crisis. But what begins as a journalistic quest to understand the science takes an abrupt and introspective turn following the death of her brother.

In the midst of grief, Hura works through science, pūrākau, poetry and back again. Seeking to understand climate change in relation to whenua and people, she asks: how should we respond to what has been lost? Her many-sided essays explore environmental degradation, social disconnection and Indigenous reclamation, insisting that any meaningful response must be grounded in Te Tiriti and anti-colonialism.

Slowing the Sun is a karanga to those who have passed on, as well as to the living, to hold on to ancestral knowledge for future generations.

Extracted from Slowing the Sun by Nadine Hura. RRP 39.99. Published by Bridget Williams Books (April 2025).

Life’s Too Short for Burning Bridges

Jimmy Barnes says that life’s too short for burning bridges, but I want to know if life will be long enough to rebuild them? When Cormac was fifteen he dropped out of Hato Pāora College, leaving the dorm and the boys behind. He came home and enrolled in the local high school, believing he could fix things that weren’t his to fix.

A year and a half later, against all expectations, he went back. In his graduation speech, he talked about the struggle to focus on school when his mind was constantly on home. He said it felt as though his world was splitting apart and he had to choose.

Speaking to the packed auditorium, he said he’d been asked many times if he had regretted leaving. But he said he couldn’t dwell on pathways not taken because the past can’t be changed, only learned from, and accepted. I knew what he meant, but regret is a song and I do so love to dance.

My niece and namesake said that the reason she went overseas was because she couldn’t see a way to repair all the things that were broken, and I don’t blame her because I’ve been there and done that, choosing flight over fight, even though I know we were both thinking the same thing: was there really nothing we could have

done?

Regret isn’t a dance. Some days it’s a treadmill. All this punishment to go nowhere.

And yet.

When I was growing up, Mum always said that if she had her time again she’d do it all differently, by which she meant she wouldn’t have married my father at the age of sixteen.

I get it, I do, but it’s hard to dissociate your own existence from the wistful look that suggests you might be the reason your parents missed out. Fewer choices, fewer chances. Less energy, less money, less education, less, less, less.

After Darren died, I took his eldest daughter back to our childhood home so she could see where we grew up. We stood at the edge of the driveway and looked. He wasn’t there, but I could see him sitting on the front steps in his red plaid shirt and black leather vest two days after Christmas, 1988. His eyes were glowing and when he smiled, he kept his lips taut to disguise that half of his front tooth was missing.

Mum’s face was flushed with the surprise of his arrival. She disappeared inside and came back with his present, chiding him that she’d been worried sick. Darren unwrapped the box in the fading light beside the bougainvillea and let Mum put the necklace around his neck. She touched her hand to his cheek and kissed him, and he hugged her back, even though his mates were sitting on the bonnet of their grey- blue Ford Cortina and laughing and guffawing.

Thirty-something years later, his daughter sniffed and said: ‘I keep questioning myself and what I did or didn’t do, but I think it goes back further than me, you know?’

I nodded, wishing it didn’t have to take the death of her father to bring her home. Surely there are easier ways to build a bridge? I remember the day she was born and how crazy-protective he had been. He made everyone wash their hands and dished out Dettol wipes before he let anyone hold her.

When we returned home to bury his ashes, we had to decide whether to return his pounamu to the soil or keep it on this side with the living.

Regret’s a commute. Same scenery, different day. I sometimes wonder where the end of the line is. What if I took it all the way back to the beginning? Past the warning signs I either missed or ignored, back through the ominous tunnel of lockdown and the years of absence. Past the footfall of a silent stepfather still echoing after all these years. Past the interracial marriage of our parents and the poverty and struggle and emigration from distant lands before that, past the prisoner-of-war camp in Hong Kong where my grandfather spent four years, past the departure of Hineāmaru’s people from Waimamaku after a rupture in the whānau, back and back and back. Has the sandfly yet begun to nip the pages of the book? Does Kāwiti regret his signature on Te Tiriti? Where even is the beginning?*

Maybe burning bridges and trains are the wrong metaphors. Time is cyclical, not linear, and bridges are for crossing. I keep hearing Cormac’s words over and over: the past can’t be changed, only accepted. When you think about it, it sounds a lot like whakapapa. We just keep making layers with memory, saying their names, telling their stories, back and back and back.

* This line references a famous prophecy by Te Ruki Kāwiti: ‘Waiho kia kakati te namu i te whārangi o te pukapuka, ko reira, ka tahuri atu ai’. Wait until the sandfly nips at the pages of the book, and at that time, you must act.’

Slowing the Sun by Nadine Hura is available in all good bookstores now.