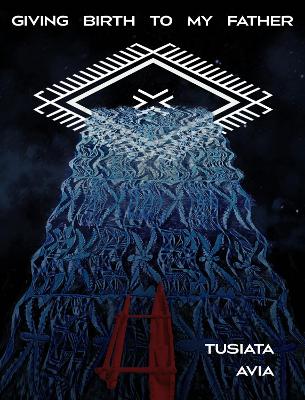

Review: Giving Birth to My Father, by Tusiata Avia

'...a rich and raw homage to her father, a deeply moving and personal reflection on his death interwoven with poignant descriptions of a daughter’s grief and family trauma.'

Tusiata Avia’s latest collection of poetry, Giving Birth to My Father, is a rich and raw homage to her father, a deeply moving and personal reflection on his death interwoven with poignant descriptions of a daughter’s grief and family trauma. The collection takes the reader on a journey from New Zealand to Samoa, from the tupuagas’ (ancestors) presence and the magic of orators performing ceremonial duties where ‘we watch the poetry glitter off his teeth’, to the mundanity of crying in a Countdown carpark and the joy of fishing for samagi (salmon) in the Waimakariri River.

In ‘I am the archaeologist’ Avia writes ‘It is all strata from the underworld up’. The archaeological metaphor is an apt device for the cataclysmic upheaval the family experiences. These poems carefully excavate and expose the shifting faultlines that slip and slide just beneath the surface of family dynamics. One powerful faultline features the ‘mean aunties’ and their brazen lobbying and political manoeuvring for authority in the power vacuum left in the wake of the father’s death. As Selina Tuistala Marsh once said, ‘Never piss off a poet.’ The follow-on being, ‘because we will write about you.’ In ‘Samoan funeral with Aunty Fale I’ Avia writes:

‘I don’t really want to write a poem about you but someone else has died and I know you will come swooping down out of the blue sky like the witch at a fairytale christening.’

The imagery used to describe this aunty is hilarious and heartbreaking at the same time. She is pushy, bossy and abusive and throws her weight around, literally.

‘You nearly pushed me into my father’s grave. I bounced off you because you are a big bitch.

And now you are thundering across the malae like the Jonah Lomu of graveyards, mourners bouncing off you left and right so you can get to your rightful place, fists full of cash and look-at me.’

Less of a faultline and more of a rift, is the common experience for diasporic Pacific peoples who move between residence and identity in New Zealand and the Pacific Islands. Having one foot in each world means you are never fully in either. For those of us in this position the rift is keenly felt at the time of a death in the family. The mean aunty features in leveraging open this rift in ‘Samoan funeral with Aunty Fale II’. She is met with angry defiance from the daughter of the deceased invoking Karen Black’s character in 1975 horror movie ‘Trilogy of Terror’ who is possessed by the spirit of a murderous voodoo doll.

‘Next time you come for me I will be waiting crouched in the corner with a machete stabbing the floor dulling the point’

Avia’s use of language is unflinchingly precise and cleanly crafted, evoking sharp imagery. ‘The entombment’ features the ‘meanest Aunty’ and made me laugh at the fate of people gathered around the father’s grave. The daughter watches as her father, who is ‘more rusty pipes than lace’, is entombed in a ‘sarcophagus-shaped hole’ with slabs of coral, and she begins to dig:

‘down to the tiny tissue-edge of my grief and anger, and all the people call out that I am hurling dirt so hard that it is crossing the mouth of the grave and hitting those who stand on the other side.’

The poem ‘In the Countdown carpark’ describes:

‘a gap in the clouds in the shape of a malu the shape of a diamond these kinds of portals always remind me of portals’

Many of the poems feature the father’s physical possessions acting as portals into his life. In ‘We read my father’s diary’ he practises his English in ‘fluid copperplate’. And in ‘Watch’, his timepiece with ‘a brown leather cover over the face’ summons not only memories of him fishing, being a freezing worker, a welder-boilermaker and a bus driver, but also summons his physical presence. There are numerous meaningful moments with the father throughout the collection. He causes earthquakes, he plays musical instruments, he is a healer, his freezing work shoulders are ‘square as Gary Cooper’s’. Perhaps a nod to Avia’s cousin Victor Rodger’s play My name is Gary Cooper.

As in Emily Dickinson’s poem ‘Tell all the truth but tell it slant’, Avia chronicles the truth of her grief in a way that is vivid, courageous and slant. In ‘Ia manuia lau malaga/Good journey’ she writes:

‘My father taught me about the importance of aunties and grandparents/ the ones here and the ones across the sea/deep in the sea of memory and in the sky/the ones I embrace with anger/ the ones I embrace with love’

This collection is a glorious celebration of Avia’s father’s life, a salute to his teachings. An embrace of family in the widest sense, even the mean aunties.