Review: The Long Shadow, by Cally Whitham

'Whitham has meticulously gathered her collection of images of native and introduced New Zealand species with the hope that a reader will look anew at our natural history and its decimation at the hands of colonists, those supreme invaders...'

New Zealand photographer Cally Whitham has childhood memories of her great-aunt's farm, and of a treasured possession passed down: a taxidermied kiwi. Propped up and displayed, it held no life or movement, but it intrigued. Whitham's ritual was to remove the casing to stroke its head. Yet its eyes would be glassy and still, no softness in its body.

This memory is highly symbolic, where the very emblem of Aotearoa New Zealand had, during colonial times, been hunted down to be captured, contained, and triumphed over. As we learn in Whitham's book, 'bushmen' would further disrespect the kiwi by consuming both its eggs and the bird itself.

Approaching The Long Shadow, a culmination of many years’ work, is an exercise in astonishment, wonder, and outraged grief. Whitham has meticulously gathered her collection of images of native and introduced New Zealand species with the hope that a reader will look anew at our natural history and its decimation at the hands of colonists, those supreme invaders. As conservationist Nicola Toki aptly describes in her foreword, what happened upon the land of Aotearoa resembles the nursery rhyme 'There was an Old Lady who Swallowed a Fly'. No good could come when species such as weasels, were brought in to control an earlier introduced species, the rabbit. Today we feel this legacy, where rabbits run rampant and vermin destroys our native birdlife. Toki asks, what does it mean for Aotearoa when our very identity has been destroyed and replaced by invaders? How can we define ourselves when we are losing our precious taonga?

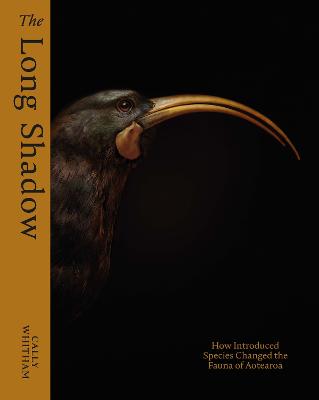

Whitham has long been fascinated both by photography (and was influenced by ancestral photos in her family) and by the wildlife around her. In this mesmerising work, where one can get lost in the images, she combines these loves. The Long Shadow contains surprisingly few words; it is the images which tell. They are startling. They are reminiscent of staged portraits from times gone, where a plaintive subject is centred, framed by enigmatic black. Each photo, much altered but with no use of AI, feels cavernous, mysterious, and strangely silent. The individual creatures peer out at the viewer with a full range of expressions but overall melancholy, resignation, and defeat dominate.

The book is split into two parts. The first looks at introduced wildlife, the context and the reasoning, and part two, particularly sombre, at our native creatures and the fallout. While those surviving have been photographed from nature as much as possible, those extinct have been drawn largely from taxidermised collections held at Te Papa and the Auckland War Memorial Museum. How ironic that an obsession with wildlife has led to its imprisonment within dusty museums - the ultimate sign of colonial conquest.

Beyond the introduction and foreword, the written content comes from firsthand sources from settler times and is telling. 'Bloodthirsty animals' and 'marauders' were largely for human consumption, sport, or extermination. Some tui were got rid of thus, 'a whole bagful of murdered tui, mere bloodstained bunches of feathers'.

Digesting such sentiments can only fill the modern-day New Zealander with horror. 'Acclimatisation Society' became a euphemism for decimation, finally admitted as 'that rash and, unfortunately, irresponsible body' when alarm bells began to clang more loudly. However, there is some comic relief in anecdotes of plagues of caterpillars greasing the road so thickly that dray wheels were as if in a puddle, or of the 'liberation' of possums as 'an item on the assets side of the ledger'. Succinct phrases amuse, of weasels with their 'thug-like brand' on victims and hopes of sheep for the country being 'blasted in a moment'. Likewise, there are accounts of kaka, kea, and weka, showing all too familiar personalities.

The images are so striking the reader will be curious about the technical process, which remains enigmatic. Whitham urges the reader to look to protecting what is left of our natural heritage and treasure it, for the 'long shadow' arches over us. This stunning illustration of where we are now at both centres our responsibility and haunts us with guilt and loss.